Teaching Bullets into Bells Behind Bars

I've been teaching College Reading and Writing--intro comp--in the Suffolk County House of Correction since November. I'm posting our lesson plans as I go. . . since we got copies of Bullets into Bells I've been using it but I'll post all the lessons.

I taught in Massachusetts prisons for 15 years, through Boston University's prison education program. People incarcerated in prisons have longer sentences, and can sign up for a traditional semester, just like a college student on campus.

One of the challenges of teaching incarcerated folks with shorter sentences is that it doesn't make sense to follow a normal academic schedule. I teach a women's section and a men's section of this class in the jail, and I've had 54 students so far. Some people were only present for a few weeks. A couple have completed all the work, and I'm working on getting them college credit. One new student came for the first time last class.

Instead of using my usual comp syllabi, where assignments build off one another and there's a longer paper at the end, I needed lessons that could challenge a brand-new student who has never heard the words "annotate" or "summarize," as well as the student who has been there and turned in strong, revised work for 15 weeks. These lessons have been working to build the confidence of students who aren't yet ready for college, and strengthen the skills of students who are earning As each week.

In addition to the lessons, which students start in class with me and revise over the week for homework, students who are ready for more are given additional assignments for longer papers, based on topics we come up with together, topics they care about. They are encouraged to use their fellow students as resources, seeing anecdotal detail and quotation as another source they can cite to support or question their own positions.

And everybody either gets an A or they get invited to revise the work and try again. Letting everyone know that I wasn't going to let anybody fail meant a lot to nervous students; I told them give it a shot, and if you don't get an A, you're just auditing the class; only all-As make you eligible for credit. That's helped boost confidence and courage, and it's done a lot to demonstrate that good writing is re-writing: everyone revises. Even me. Especially me.

For those students who do enough strong writing to deserve credit, the syllabus looks like this.

I taught in Massachusetts prisons for 15 years, through Boston University's prison education program. People incarcerated in prisons have longer sentences, and can sign up for a traditional semester, just like a college student on campus.

One of the challenges of teaching incarcerated folks with shorter sentences is that it doesn't make sense to follow a normal academic schedule. I teach a women's section and a men's section of this class in the jail, and I've had 54 students so far. Some people were only present for a few weeks. A couple have completed all the work, and I'm working on getting them college credit. One new student came for the first time last class.

Instead of using my usual comp syllabi, where assignments build off one another and there's a longer paper at the end, I needed lessons that could challenge a brand-new student who has never heard the words "annotate" or "summarize," as well as the student who has been there and turned in strong, revised work for 15 weeks. These lessons have been working to build the confidence of students who aren't yet ready for college, and strengthen the skills of students who are earning As each week.

In addition to the lessons, which students start in class with me and revise over the week for homework, students who are ready for more are given additional assignments for longer papers, based on topics we come up with together, topics they care about. They are encouraged to use their fellow students as resources, seeing anecdotal detail and quotation as another source they can cite to support or question their own positions.

And everybody either gets an A or they get invited to revise the work and try again. Letting everyone know that I wasn't going to let anybody fail meant a lot to nervous students; I told them give it a shot, and if you don't get an A, you're just auditing the class; only all-As make you eligible for credit. That's helped boost confidence and courage, and it's done a lot to demonstrate that good writing is re-writing: everyone revises. Even me. Especially me.

For those students who do enough strong writing to deserve credit, the syllabus looks like this.

Prof.

Jill McDonough

College

Reading and Writing

Suffolk

County House of Corrections at South Bay

2017-2018

Mondays:

Women 6:30pm-7:30pm, Men 7:30pm-9pm

Goals of the course: This course is for students who want to

improve their skills in reading, writing, and critical thinking. You will read and analyze examples of

effective writing, develop and articulate your ideas about them, and learn how

to use their strengths to your advantage. You will produce long and short

writing assignments that establish a clear thesis and support it with strong

evidence and analysis.

It’s

difficult to offer a traditional semester-long class in jail, where people

begin and end their sentences at different times. All are welcome to audit this college class; those

students who are here long enough to do a semester’s worth of work, and do all

the work, are eligible for credit.

Reading and discussion:

I’ll

be bringing in handouts of poems and short stories; we’ll also use copies of

Bullets into Bells: Poets and Citizens Repond to Gun Violence. We’ll be using

these texts to develop your ideas while you study grammar, sentence structure,

and punctuation. Read carefully, and come to class with notes, ideas, comments,

and questions. Participation is an important part of the class, and an

opportunity for you to articulate your ideas while developing critical

listening skills.

Written work: In addition to the shorter weekly assignments,

students seeking credit for this course will work with me one-on-one to develop

a longer argument paper, 5-7 pages. The topics will be suggested by the

reading, but the specific direction of your essays will be up to you. You’ll express an opinion, or make an

observation, and work to support your ideas with evidence from the text.

In

developing this longer essay, you will be writing several shorter pieces, and

at least one draft and revision of the complete essay. A successful essay does not appear overnight:

it requires extensive revision through multiple drafts. You’ll begin with rough sketches of your

ideas, figuring out what you think and how to articulate it. Through successive drafts you’ll refine this

work, until you are ready to write to an audience, anticipating and developing

readers’ responses to your ideas. Over

the course of our time together we will move from helping you articulate your

own ideas to crafting work that is clear and meaningful to its readers. For each homework assignment, you’ll do brief

“pre-draft” assignments in class, in which you brainstorm ideas and set down

the basic parts of your argument. Then

you’ll complete and turn in a draft, which we’ll work on together. This draft should not be your first attempt,

but a complete, full-length essay. After

receiving feedback, you’ll respond with a revision that demonstrates

substantial effort and re-thinking of your work. We’ll discuss how superficial, editorial

changes—such as deleting a troubled sentence or merely addressing errors in

punctuation—are insufficient responses to the revision assignment.

Paper format: You will each receive a composition book for

notes and drafts; this is yours to keep; don’t put your finished work in it and

hope to turn it in to me. I’ll hand out

loose-leaf paper and blue books for your homework assignments. All papers must

have a Works Cited page; we’ll talk about how to format this.

Grading:

Class

participation and preparatory assignments: 60%

Longer

essay: 40%

Work

that is not up to the standard of A will not be graded. I will mark it and

encourage you to revise the work until it earns an A, and you can revise it as

many times as you like. If your work isn’t

strong enough to earn an A in this class, you are just auditing the

course. A lot of incarcerated people are

nervous about taking their first college class, worried they aren’t ready. I want to give you all a boost and relieve

your worries to encourage all of you to do your best. There

is no way to fail this course; you will either earn an A and be

eligible for credit, or you are just practicing, auditing the course, improving

your work and getting ready for college.

All

of the lesson plans are available at jailmcdonough.blogspot.com

Week 1: Elizabeth Bishop. Annotation,

Summary, In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 2: Ellen Bass. Comparing texts. Recognizing motive. Annotation, Summary,

In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 3: Jacqueline Woodson. Developing a thesis. Annotation, Summary,

In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 4: George Saunders.Argument and Counterargument.

Annotation, Summary, In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 5: Krysten Hill. Claim, Evidence, Analysis. Annotation,

Summary, In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 6: Natasha Trethewey. Annotation, Summary,

In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 7: Reginald Dwayne Betts. Close Reading. Annotation,

Summary, In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 8: Clint Smith summary. Punctuation,

paraphrasing. Annotation, Summary, In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 9: Clint Smith in full. Developing

thesis statements. Annotation, Summary, In-text Citation, Analysis, and

Imitation. Semicolon exercises.

Week 10: Jack Gilbert. Exercises in

sentence and paragraph revision. Annotation, Summary, In-text Citation,

Analysis, and Imitation

Week 11: Robert Pinsky. Revision

exercises. Annotation, Summary, In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 12: Louise Glück. Annotation,

Summary, In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 13: Arnold and McBath. Annotation,

Summary, In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 14: Baca and Wiriadjaja. Annotation,

Summary, In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 15: Barnes and Richardson. Annotation,

Summary, In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 16: Betts and Rice. Annotation,

Summary, In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

Week 17: Blanco and Everitt. Annotation,

Summary, In-text Citation, Analysis, and Imitation

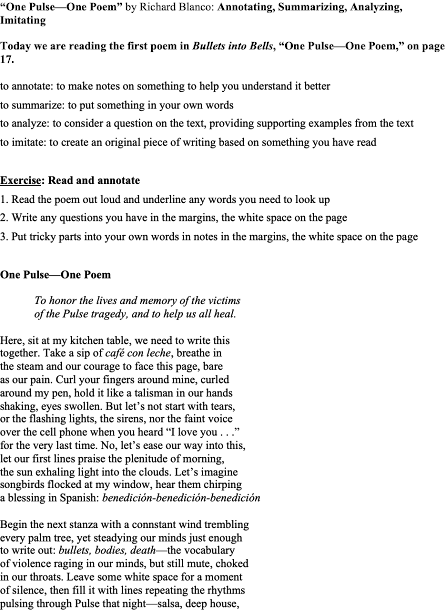

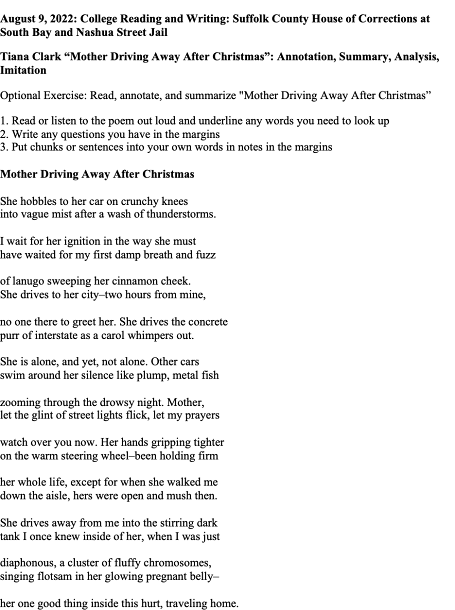

Week 1: College Reading and Writing: Suffolk County House of Corrections at South Bay

ReplyDeleteAnnotating and Summarizing a text

to annotate: to make notes on something to help you understand it better

to summarize: to put something in your own words

For discussion: what are some things you read? What are some things you have read or seen or heard that you found difficult to understand? What did you do to help yourself understand it better?

Exercise: Summarize a movie you've seen for a friend who hasn't seen it. Let's try it with Jaws.

Exercise: Read, annotate, and summarize "One Art" by Elizabeth Bishop

1. Read the poem out loud and underline any words you need to look up

2. Write any questions you have in the margins

3. Put tricky sentences into your own words in notes in the margins

4. Write a paragraph summarizing the poem in your own words, with quotations from the poem.

One Art

Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979)

The art of losing isn't hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother's watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn't a disaster.

--Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan't have lied. It's evident

the art of losing's not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.