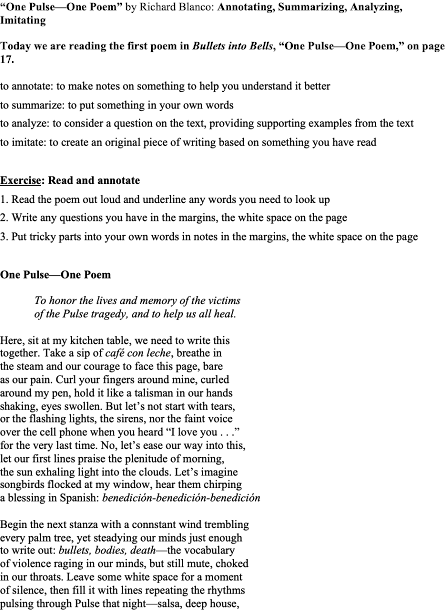

Week 58: College Reading and Writing: Matthew Shaer

Week 58:

College Reading and Writing: Matthew Shaer

Matthew

Shaer: Annotating, Summarizing, Analyzing, Imitating

to annotate: to make notes on something to help

you understand it better

to summarize: to put something in your own words

to analyze: to consider a question on the text,

providing supporting examples from the text

to imitate: to create an original piece of

writing based on something you have read

Exercise:

Read and annotate

1. Read the article out loud and underline any

words you need to look up

2. Write any questions you have in the margins or

in your notebook

3. Put tricky parts into your own words in notes

in the margins or in your notebook

Exercise:

Questions for comprehension of the article

1. How are the criminal justice system and taxes

related?

2. Who is considered poor in this article?

3. Who is the narrator in this article? Why is it

important?

Exercise:

Summarize the article

Write a paragraph summarizing the article with

quotations, in-text citation, and a Work Cited Page.

Example

too-short summary, incorporating quotation and in-text citation:

Brenda Hillman’s poem “The Family Sells the

Family Gun” tells the story of siblings getting rid of their father’s gun after

“his ashes...were lying” (87). The speaker questions what it means to own and

get rid of a gun in America, saying, “[w]e couldn’t take it to the cops even in

my handbag” (Hillman 88).

Work Cited

Page (for today’s article)

Shaer, Matthew. “How

Cities Make Money by Fining the Poor.” The New York Times Magazine, The New York Times, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/08/magazine/cities-fine-poor-jail.html

Exercise:

Analysis

Question for analysis: Mitali

Nagrecha says, “You think about what we want to define us as Americans: equal

opportunity, equal protection under the law,” do you agree with Nagrecha about

what we want to define us as Americans? Is that how you would want to define

Americans? Why or why not? This is a New York Times

Magazine Article. The writing is journalism, does that change the way you read

it? What do you think the author wants the reader to do? Who is this article

written for?

Exercise:

Imitation

Write about an event where you were doing one

thing and someone made a mistake and thought you were doing something wrong.

Maybe you were trying on a hat in a store and a salesperson thought you were

stealing it. Maybe you were driving while black. Maybe you were rough-housing

with a friend and someone thought you were fighting. You are the expert on you.

Use elements from Shaer’s article that you admire to make your own story

stronger.

Homework:

1. Summary

of Article

2. Analysis

of Article

3.

Imitation of Article

About this

class:

Your notebooks belong to you; you can write first

drafts in them, and make notes for yourselves.

To turn in homework, revise your work in a blue book or sheets of paper

you can get from your instructor. In this class, you are welcome to submit

homework for a grade. If it’s not strong enough to earn an A, I’ll give you

some comments to help you revise it, and let you do it over again. You have as

many chances as you want to complete and perfect the work in this class, and

you are welcome to do more than one week’s worksheet for homework at a time;

ask me for sheets you’ve missed. Students who complete 15 weeks of graded

assignments and a longer paper can qualify for college credit. When you get

close to completing 15 weeks, I’ll help you get started on your longer paper.

How Cities Make Money by Fining the Poor (Part 1)

By Matthew Shaer

On a muggy afternoon in October 2017, Jamie Tillman walked into

the public library in Corinth, Miss., and slumped down at one of the computers

on the ground floor. In recent years, Tillman, who is slight and freckled, with

reddish blond hair that she often wears piled atop her head, had been drifting

from her hometown, Nashville — first to southern Tennessee, to be with a

boyfriend and their infant son, and then, after she and the boyfriend split,

across the state border to Corinth to look for work. The town, to Tillman,

represented a chance for a turnaround. If she was able to get a part-time job

at a big-box store, she could put a deposit on a rental apartment and see a

psychiatrist for what she suspected was bipolar disorder. She could take steps

toward regaining custody of her son from her boyfriend’s mother. “I needed to

support myself,” she told me recently. But potential employers weren’t calling

her back, and Tillman was exhausted. In the hushed calm of the library, she

closed her eyes and fell asleep.

When she awoke, a pair of uniformed police officers were

standing over her. “I was terrified,” she recalled. “I couldn’t figure out what

was happening.” (Library patrons had complained about her behavior.) Ignoring

Tillman’s protests that she wasn’t drunk — she was just scared and tired, she

remembers saying — the officers handcuffed her wrists behind her back and took

her to the jail in Corinth to await a hearing on a misdemeanor charge of public

intoxication. Five days later, clad in an orange jumpsuit, her wrists again

cuffed, Tillman found herself sitting in the gallery of the local courthouse,

staring up at the municipal judge, John C. Ross.

Tillman did her best to stay calm. She had been arrested on

misdemeanor charges before — most recently for drug possession — and in her

experience, the court either provided defendants with a public defender or gave

them the option to apply for a cash bond and return later for a second hearing.

“But there was no lawyer in this courtroom,” Tillman says. “There was no one to

help me.” Instead, one after another, the defendants were summoned to the bench

to enter their pleas and exchange a few terse words with Ross, a white-haired,

pink-cheeked Corinth native who dismissed most of them with the same four

words: “Good luck to you.” Many of the defendants were being led back out the

way they came, in the direction of the jail.

Around 11 a.m., the judge read Tillman’s name. She stood. “Ms.

Tillman, you’re here on a public drunk charge,” Ross said. “Do you admit that

charge or deny it?”

Tillman told me that she thought she had no

choice but to plead guilty — it was unlikely, she believed, that the judge

would take her word over that of the arresting officers. “I admit, your honor,”

she said. “I just want to get me out of here as soon as possible.” Under

Mississippi state law, public intoxication is punishable by a $100 fine or up

to 30 days in jail. Ross opted for the maximum fine. Tillman began to cry.

The Federal Reserve Board has estimated that 40

percent of Americans don’t have enough money in their bank accounts to cover an

emergency expense of $400. Tillman didn’t even have $10. She couldn’t call her

family for help. She was estranged from her father and from her mother, who had

custody of Tillman’s two young daughters from a previous relationship.

“I can’t — ” Tillman stammered to Ross. “I can’t — ”

Ross explained the system in his court: For every day a defendant

stayed in the Alcorn County jail, $25 was knocked off his or her fine. Tillman

had been locked up for five days as she awaited her hearing, meaning she had

accumulated a credit of $125 toward the overall fine of $255. (The extra $155

was a processing fee.) Her balance on the fine was now $130. Was Tillman able

to produce that or call someone who could?

“I can’t,” Tillman responded, so softly that the court recorder

entered her response as “inaudible.” She tried to summon something more

coherent, but it was too late: The bailiff was tugging at her sleeve. She would

be returned to the jail until Oct. 14, she was informed, at which point Ross

would consider the fine paid and the matter settled.

That night, Tillman says, she conducted an informal poll of the

20 or so women in her pod at the Alcorn County jail. A majority, she says, were

incarcerated for the same reason she was: an inability to pay a fine. Some had

been languishing in jail for weeks. The inmates even had a phrase for it:

“sitting it out.” Tillman’s face crumpled. “I thought, Because we’re poor,

because we’re of a lower class, we aren’t allowed real freedom,” she recalled.

“And it was the worst feeling in the world.”

No government

agency comprehensively tracks the extent of criminal-justice debt owed

by poor defendants, but experts estimate that those fines and fees total tens

of billions of dollars. That number is likely to grow in coming years, and

significantly: National Public Radio, in a survey conducted with the Brennan

Center for Justice and the National Center for State Courts, found that 48

states increased their civil and criminal court fees from 2010 to 2014. And

because wealthy and middle-class Americans can typically afford either the

initial fee or the services of an attorney, it will be the poor who shoulder

the bulk of the burden.

“You think about what we want to define us as

Americans: equal opportunity, equal protection under the law,” Mitali Nagrecha,

the director of Harvard’s National Criminal Justice Debt Initiative, told me. “But

what we’re seeing in these situations is that not only are the poor in the

United States treated differently than people with means, but that the courts

are actually aggravating and perpetuating poverty.”

Why they do so is in part a matter of economic

reality: In areas hit by recession or falling tax revenue, fines and fees help

pay the bills. (The costs of housing and feeding inmates can be subsidized by

the state.) As the Fines and Fees Justice Center, an advocacy organization based in New

York, has documented, financial penalties on the poor are now a leading source

of revenue for municipalities around the country. In Alabama, for example, the Southern

Poverty Law Center took up the case of a woman who was jailed for missing a

court date related to an unpaid utility bill. In Oregon, courts have issued

hefty fines to the parents of truant schoolchildren. Many counties around the

country engage in civil forfeiture, the seizure of vehicles and cash from

people suspected (but not necessarily proven in court) of having broken the

law. In Louisiana, pretrial diversion laws empower the police to offer traffic

offenders a choice: Pay up quickly, and the ticket won’t go on your record;

fight the ticket in court, and you’ll face additional fees.

“What we’ve seen in our research is that the

mechanisms vary, depending on the region,” says Joanna Weiss, co-director of

the Fines and Fees Justice Center. “But they have one thing in common: They use

the justice system to wring revenue out of the poorest Americans — the people

who can afford it the least.” Aside from taxes, she says, “criminal-justice

debt is now a de facto way of funding a lot of American cities.”

Comments

Post a Comment