Week 59: College Reading and Writing: Matthew Shaer

Week 59: College Reading and Writing: Matthew Shaer

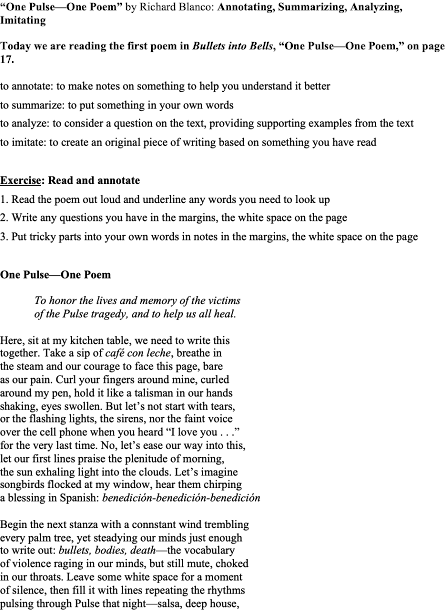

Matthew Shaer: Annotating, Summarizing, Analyzing, Imitating

to annotate: to make notes on something

to help you understand it better

to summarize: to put something in your

own words

to analyze: to consider a question on the

text, providing supporting examples from the text

to imitate: to create an original piece

of writing based on something you have read

Exercise: Read and annotate

1. Read the article out loud and

underline any words you need to look up

2. Write any questions you have in the

margins or in your notebook

3. Put tricky parts into your own words

in notes in the margins or in your notebook

Exercise: Questions for comprehension of the article

1. Who does not comment in this article?

2. How many Corinth residents give

testimonials?

3. Who is Judge John C. Ross? Why is he

important?

Exercise: Summarize the article

Write a paragraph summarizing the article

with quotations, in-text citation, and a Work Cited Page.

Example too-short summary, incorporating quotation and in-text

citation:

Brenda Hillman’s poem “The Family Sells the

Family Gun” tells the story of siblings getting rid of their father’s gun after

“his ashes...were lying” (87). The speaker questions what it means to own and

get rid of a gun in America, saying, “[w]e couldn’t take it to the cops even in

my handbag” (Hillman 88).

Work Cited Page (for today’s

article)

Shaer, Matthew.

“How Cities Make

Money by Fining the Poor.” The New

York Times Magazine, The New York

Times, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/08/magazine/cities-fine-poor-jail.html

Exercise: Analysis

Question for analysis: Why do you think

Corinth is used as the primary example in this article? What makes Corinth

special? Is Corinth a “universal” city? How does your own experience compare

with the examples in Corinth? Remember

to use quotation and citation as you support your points.

Exercise: Imitation

Write about a place that is important to

you. A place is made up of location, locale, and sense of place. Location is

the where: the corner of Dennis and Washington, the park on the hill

overlooking Dorchester, exit 15 on I-93 S. Locale is the context or situation:

a school, or jail, or family home. And the sense of place is your experience,

what makes it important to you. Use elements from Shaer’s article that you

admire to make your own story stronger.

Homework:

1. Summary of Article

1. Analysis of Article

1.

Imitation of

Article

About this class:

Your notebooks belong to you; you can

write first drafts in them, and make notes for yourselves. To turn in homework, revise your work in a

blue book or sheets of paper you can get from your instructor. In this class,

you are welcome to submit homework for a grade. If it’s not strong enough to

earn an A, I’ll give you some comments to help you revise it, and let you do it

over again. You have as many chances as you want to complete and perfect the

work in this class, and you are welcome to do more than one week’s worksheet

for homework at a time; ask me for sheets you’ve missed. Students who complete

15 weeks of graded assignments and a longer paper can qualify for college

credit. When you get close to completing 15 weeks, I’ll help you get started on

your longer paper.

How Cities Make Money by Fining the Poor (Part 2)

By Matthew Shaer

Corinth occupies an important place in

Mississippi history. During the Civil War, the South lost two bloody battles

trying to defend the rail lines that bisected the city, which Confederate

leaders regarded as second only to Richmond, their capital, in terms of

strategic importance. Today the rails remain, as do the battlefield and a

handful of grand antebellum homes, but driving around the area, you get a sense

that the place has been hollowed out. As of 2016, a quarter of the 14,600

residents, 70 percent of whom are white, lived at or below the federal poverty

line (about $12,000 in annual income for an individual).

Drug use is endemic —

primarily opioids and methamphetamine. So, too, are the hallmarks of a specific

kind of rural, Southern poverty: stray dogs in the streets, sun-blasted

trailers that seem to be sinking back into the earth, yards occupied by rusting

school buses and old sedans. “You grow up around here, and you have two

options,” one resident told me. “You can either get the hell out, go on up to

Tupelo or wherever. Or you stay and try to figure out a way to live without

having the cops on you all the time. Which sure ain’t easy.”

Corinth’s infrastructure

runs so leanly as to be almost invisible: There are no public buses, and Alcorn

County recently announced that it would stop funding the local railroad museum.

Tax rates in Corinth have dropped slightly in recent years, while the

percentage of revenue generated by criminal-justice-related debt has grown.

According to the annual audit submitted by Corinth to the state, in fiscal year

2017, the year Jamie Tillman was arrested for public intoxication, general fund

revenues for the city were just $10.8 million. Total revenue for the year was

$20.3 million, half of which came from taxes; close to $7 million came from

“intergovernmental revenue,” or grants and funds from the state and federal

authorities. And approximately $623,000 came from what the city defines as

“fines and forfeitures.”

The Corinth city clerk

declined to answer questions about the breakdown of the budget or how the

revenue from fines compares with those of neighboring towns, referring

questions to the city attorney, Wendell Trapp, who did not respond to emails

seeking comment. But a report completed in 2017 by the U.S. Commission on Civil

Rights offers some answers. Combing Census Bureau data and city audit

documents, the commission noted that of nearly 4,600 American municipalities

with populations above 5,000, the median received less than 1 percent of their

revenue from fines and fees. But a sizable number of cities, like Doraville,

Ga., or Saint Ann, Mo., a suburb of St. Louis, have reported fines-and-fees

revenue amounting to 10 percent or more of total municipal income.

Corinth’s revenue from

fines in 2017 was 5.7 percent of its general fund revenues, putting it — if not

quite at the Saint Ann level — at the high end when compared with the

municipalities in the Commission on Civil Rights’s report. When I sent Joanna

Weiss, of the Fines and Fees Justice Center, a copy of the 2017 Corinth audit,

she noted that this would be dismaying enough in itself. “But you can also

see,” she added, “that the biggest expenditure, by far, for the city of Corinth

is public safety” — including court and police services, or the very people

extracting the fines.

In 2017, Micah West and

Sara Wood of the S.P.L.C. drove to Corinth to open an investigation into the

Municipal Court, with an eye toward later filing a lawsuit — the most effective

way, they believed, to halt Judge John C. Ross’s jailing of low-income

defendants. During court sessions, they would often walk down the hall to the

clerk’s office, where defendants were permitted to use a landline phone to make

a final plea for the cash that would set them free. The space amounted to an

earthly purgatory: Secure the money, and you were saved. Fail, and you’d be

sent to jail. “All around us, people would be crying or yelling, getting more

and more desperate,” Wood recalled.

That October, she watched a

59-year-old man named Kenneth Lindsey enter the office, his lean arms hanging

lank by his side, his face gaunt and pale. Lindsey had been in court for

driving with an expired registration, but he hadn’t been able to afford the

fines: He was suffering from hepatitis C and liver cancer, and he had spent the

very last of his savings on travel to Tupelo for a round of chemotherapy. Until

his next state disability check arrived, he was broke. “Can you help?” Lindsey

whispered into the phone.

A few seconds of silence

passed. “All right, then. Thanks anyway.”

Finally, around 1:45 p.m.,

Lindsey managed to get through to his sister. She barely had $100 herself, but

she promised to drive it over after her shift was through.

Wood caught up with Lindsey

in the parking lot later that day, and after identifying herself, asked if he

would consider being interviewed by the S.P.L.C. “I don’t know,” Lindsey said,

studying the ground. But soon enough, he called Wood to say he had changed his

mind. “I’ve been paying these sons of bitches all my life,” he told her. “It’s

time someone did something about it.”

Traveling around Corinth,

Wood found that nearly everyone she met had experience with the local courts or

could refer her to someone who did. Soon her voice mail inbox filled with

messages from people who wanted to share their stories. The callers were

diverse in terms of age and race. They were black and white; they were young

and old. But they shared with Kenneth Lindsey a precipitous relationship to

rock-bottom poverty. If not completely destitute, they were close — a part-time

job away from homelessness, a food-stamp card away from going hungry.

There was the man who

couldn’t read and hadn’t said a word until he was 5 years old. Not long after

his 35th birthday, he was arrested for public drunkenness. When he got in touch

with Wood, he had been in jail for three days, unable to decipher the charging

documents filed against him or figure out a way to access his disability check

— his lone source of income.

There was the woman,

Latonya James, with a daughter who had been intentionally scalded with boiling

water by her stepmother as an infant; now a teenager ashamed of the scars that

covered her chest and neck, the girl had stopped going to her high school. The

city charged James, then living in a home without electricity or running water,

with truancy, on her daughter’s behalf, and Judge Ross ordered her to pay $100

of the $163 fine or go to jail. (She managed to scrape together the money.)

And there was Glenn

Chastain, who owed $1,200 for expired vehicle tags — and, because he had missed

one hearing, was denied the chance to pay a partial fine. Chastain spent 48

days at the Alcorn County Correctional Facility. He said he was in a unit

occupied by accused rapists and murderers and was beaten by inmates until his

ribs were bruised and his face was a mask of blood. He smiled to show me where

one of his teeth had been knocked out. (Alcorn County authorities offered no

comment on the fight.)

Comments

Post a Comment