Week 60: College Reading and Writing: Matthew Shaer

Week 60: College Reading and Writing: Matthew Shaer

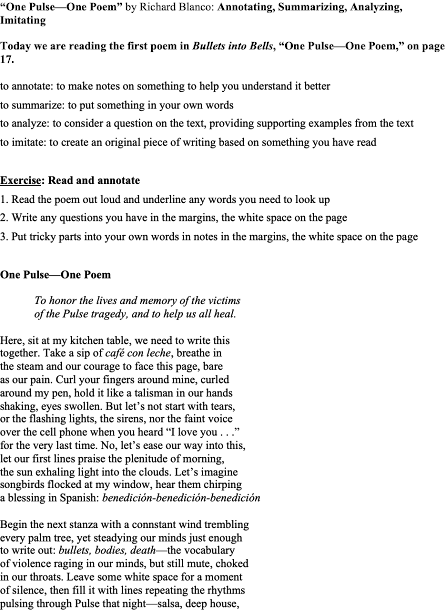

Matthew Shaer: Annotating, Summarizing, Analyzing, Imitating

to annotate: to make notes on something

to help you understand it better

to summarize: to put something in your

own words

to analyze: to consider a question on the

text, providing supporting examples from the text

to imitate: to create an original piece

of writing based on something you have read

Exercise: Read and annotate

1. Read the article out loud and

underline any words you need to look up

2. Write any questions you have in the

margins or in your notebook

3. Put tricky parts into your own words

in notes in the margins or in your notebook

Exercise: Questions for comprehension of the article

1. What is wealth-based detention? Is it

legal?

2. How will Judge John C. Ross rule in

the future?

3. Who is Rebecca Phipps? Why is she

important?

Exercise: Summarize the article

Write a paragraph summarizing the article

with quotations, in-text citation, and a Work Cited Page.

Example too-short summary, incorporating quotation and in-text

citation:

Brenda Hillman’s poem “The Family Sells the

Family Gun” tells the story of siblings getting rid of their father’s gun after

“his ashes...were lying” (87). The speaker questions what it means to own and

get rid of a gun in America, saying, “[w]e couldn’t take it to the cops even in

my handbag” (Hillman 88).

Work Cited Page (for today’s

article)

Shaer, Matthew.

“How Cities Make

Money by Fining the Poor.” The New

York Times Magazine, The New York

Times, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/08/magazine/cities-fine-poor-jail.html

Exercise: Analysis

Question for analysis: This article is

about poor people going to jail because they can not pay fines. I think it is wrong to jail people who can

not pay fines; a payment plan or community service seems like a reasonable

alternative. What do you think? How does your own experience compare with the

examples in Corinth? Remember to use

quotation and citation as you support your points.

Exercise: Imitation

Write

about being stuck between a rock and a hard place. Kenneth Lindsey said that

“Hitchhiking scared him, and he didn’t want to bother his friends more than he

had to” (Shaer). When in your life have

you felt stuck like that? Maybe you had to take your grandma to the hospital,

but had a date scheduled with the love of your life; maybe you wanted to go to

school on time, but had to drop off your younger sibling; maybe you wanted to

make dinner, but there was no food in the house and no money in your bank

account. Use elements from Shaer’s article that you admire to make your own

story stronger.

Homework:

1. Summary of Article

1. Analysis of Article

1.

Imitation of

Article

About this class:

Your notebooks belong to you; you can

write first drafts in them, and make notes for yourselves. To turn in homework, revise your work in a

blue book or sheets of paper you can get from your instructor. In this class,

you are welcome to submit homework for a grade. If it’s not strong enough to

earn an A, I’ll give you some comments to help you revise it, and let you do it

over again. You have as many chances as you want to complete and perfect the

work in this class, and you are welcome to do more than one week’s worksheet

for homework at a time; ask me for sheets you’ve missed. Students who complete

15 weeks of graded assignments and a longer paper can qualify for college

credit. When you get close to completing 15 weeks, I’ll help you get started on

your longer paper.

How Cities Make Money by Fining the Poor (Part 3)

By Matthew Shaer

Starting in October, with

West in Corinth and his boss, Sam Brooke, in Montgomery, the S.P.L.C. set about

drafting the lawsuit, which accused Ross of “wealth-based detention.” The

Corinth court had done more than violate the Constitution, the attorneys wrote.

It had broken state law, which says that “incarceration may be employed only

after the court has conducted a hearing and examined the reasons for nonpayment

and finds, on the record, that the defendant was not indigent or could have

made payment but refused to do so.” Ross, they asserted, had never bothered to

ask for that information.

A few months ago, I found

Kenneth Lindsey standing on the porch of his home in Corinth, dressed in faded

jeans and a shirt that was mostly unbuttoned, exposing the thin gold chain

around his neck. The house had belonged to his mother, he confessed, and he

hadn’t messed around much with the decorating since she died — the place, a

converted double-wide trailer, was full of old family photos. He plummeted into

a reclining armchair with a sigh.

Theoretically, he

explained, his liver cancer was in remission, although he acknowledged he had

no concrete proof. In the time since his first conversation with Wood, he had

been back and forth to jail two more times, and he had been to the hospital in

Tupelo just once. “I would estimate that I’ve spent a quarter of the last year

behind bars,” he told me. Could he calculate exactly what he owed? “$10,000?”

he responded. “$11,000?” The way he said it, it might as well have been a million

dollars. “I ain’t never going to pay it down,” he said. “Never, ever. I’m going

to be paying it down until I die.”

Rummaging in his bedroom

closet, he produced a cardboard box, which he upended onto his bed. A blizzard

of documents spilled out: tickets and warnings and second warnings and court

summons. I picked one up at random. It dated back to 2005. “Now you’re getting

the idea,” Lindsey said.

Nearly every one of

Lindsey’s court fees related, in one way or another, to his vehicle: expired

registration fees, expired driver’s licenses. He couldn’t pay for the right

paperwork or pay down his fines, but he couldn’t stop driving either, because

driving was how he got to the auto body shop where he picked up the odd shift.

Hitchhiking scared him, and he didn’t want to bother his friends more than he

had to. “My pride gets in my way a lot,” Lindsey told me. “They’re not

embarrassed by you wanting their help, but you are.”

We returned to the living

room. Lindsey propped open the door. It wasn’t yet bug season; a fragrant

breeze blew through the room. “Maybe they should investigate why they end up

picking on the same damn people all the time,” he said. “Why is it us? Tell me

that: Why is it us?”

In early December 2017, the S.P.L.C. and the

MacArthur Justice Center filed their lawsuit against Corinth. That same month,

the city ordered the jail emptied of all inmates incarcerated for nonpayment of

fines. “There was no explanation,” says Brian Howell, one of the lawsuit’s

plaintiffs, who was then incarcerated, sitting out $1,250 in fines and court

costs for three unpaid traffic tickets. “It was just, ‘All right, get up and

go.’ ”

Howell is 29, with watery

blue eyes and freckled cheeks. Years ago, he was struck by a drunken driver

while riding his motorcycle; he lost one leg and suffered extensive nerve and

spinal damage. It is hard for him to walk, let alone play with his three

children, without the aid of crutches. But the guards at the jail wouldn’t lend

him a pair. Nor would they give him a ride home. The best they would offer was

a lift across the street, to the gas station. From there, Howell began scooting

on his buttocks along the side of the road, using his hands to haul himself

forward. Soon his forearms were sore, his fingertips bloody. A police cruiser

pulled up alongside him. “The guy looks over, and he just busts out laughing,”

Howell recalled last spring. Howell is extremely soft-spoken, and when he told

me what the cop said to him, I was certain I’d misheard. He repeated it more

loudly: “He said, ‘Hell, I thought you was a damn dog.’ ”

Later that day, as a rare

early-spring snowstorm settled over Alcorn County, I drove across town to the

modest home that serves as the offices and personal residence of Judge John C.

Ross. The roads were empty, with all local schools and most local businesses

shut, and as I pulled into Ross’s driveway, my rental car noisily skidded; by

the time I’d shifted into park, the judge was at the door, a hand raised in

greeting.

“Come in, come in,” he

said, without asking what I wanted. When I told him I was a reporter, he smiled

broadly. “Well, you’ll have to stay at least until you’re all warmed up.”

He led me down a hallway,

past a framed drawing of the first Battle of Corinth — he found it in an old

edition of Harper’s Weekly, he explained — and into the sun-washed living room

that doubles as his office. On the shelves around us were history books and

leather-bound novels by Hemingway. “I was an English major in college,” Ross

said. He guided me to a chair. “Sit, sit, sit. Let’s talk.”

Ross was not the only

target of the lawsuit — the city of Corinth was named, too — and he had

received specific instructions from attorneys not to directly discuss it.

Still, there were things the judge felt he could say: Both entities, he said,

had consented to put a temporary hold on the policy of jailing indigent

defendants, and incarceration in many cases would be replaced with payment

plans or community-service opportunities. “I intend to abide by that

settlement,” he said.

He spoke of his time at Ole

Miss, his matriculation into the university’s law school and his decades in

private practice. He talked about those decades in a way that made clear he

regarded his more recent stint as a Municipal Court judge as something other

than the crowning achievement of his legal career. But he had accepted it out

of a sense of duty to the place he grew up. “Outside of school and an early

job, I’ve never lived anywhere else but Corinth,” he said. “I love the people,

and I love the place. And I don’t think I’ll ever leave.” He sometimes worked

as an administrator for the cemetery across the street, and in retirement,

that’s where he planned to spend some of his days.

Ross was sitting with his

back to a large picture window, and behind him, through the glass, wet snow was

falling on the oak tree in his backyard. As politely as he had shown me in, he

showed me out again — he and his friends had plans to visit New Orleans that

weekend, and there was packing to be done. As I shook Ross’s hand, I was reminded

of the taxonomy of municipal judges that Sam Brooke of the S.P.L.C. had laid

out for me. “I’d split them into camps,” Brooke said. “The first are the ones

that respect the law. The second are the vindictive ones, who see every

defendant as a bad person in need of punishment. But the biggest group are

judges who are part of the retail industry of processing a whole lot of people.

They’re just doing what the judges before them did.”

In July, a U.S. district judge finalized the

temporary policy Corinth and the S.P.L.C. had agreed to regarding indigent

defendants. “Nothing in this says poor people don’t have to obey the law or pay

their fines,” Cliff Johnson of the MacArthur Justice Center told The Associated

Press at the time. “They just get additional time to pay their fines and don’t

have to go to jail because they’re poor.”

In June, Ross announced his

retirement; this fall, he was replaced on the municipal bench by Rebecca

Phipps, a judge who worked for 40 years as an attorney in Corinth, and who was

briefed on the terms of the settlement before accepting the job. After lobbying

by the S.P.L.C. and the A.C.L.U., both houses of the State Legislature

unanimously passed a bill prohibiting any resident from being jailed for a

failure to pay either court costs or fines. The bill went into effect in July

of last year.

Comments

Post a Comment